On 10 February 2006, Broadview Press released a version of H. Rider Haggard's She (1886). The cover of this edition ![[image of a mummified woman]](wp-content/uploads/2009/06/She_Broadview.jpg) is interesting, in large part because it is almost perfectly wrong. I'll explain what's wrong with the use of the image of this mummy by comparing and contrasting She with, well, the Mummy.

is interesting, in large part because it is almost perfectly wrong. I'll explain what's wrong with the use of the image of this mummy by comparing and contrasting She with, well, the Mummy.

In many respects, the movie The Mummy (1932) is a retelling of She. Consider the two title characters. Ayesha is about 2000 years old; Imhotep about 3700 years old. Ayesha has been living in a tomb for most of those centuries; Imhotep has been sealed in a sarcophagus. Each was thus consigned by a wrongful act associated with love. Each seeks over all else to be reünited with the reïncarnation of the one whom he or she loved those many centuries earlier. To effect that reünion, each must transform the loved one as Ayesha or as Imhotep have been transformed, but the loved one shrinks from the transformation, and as a consequence Time catches-up with Ayesha and with Imhotep. Each has and uses the ability to kill by some dreadful mesmeric power. Both Ayesha and Imhotep face young rivals in love (Ustane and Frank, respectively), and are willing to use their dreadful power to destroy those rivals.

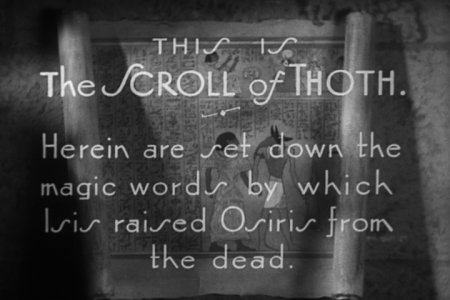

There are more minor echoes. Ayesha uses a vessel of water in her chambers as a device to see things elsewhere and of other times:

Then gaze upon that water,

and she pointed to the font-like vessel, and then, bending forward, held her hand over it.

I rose and gazed, and instantly the water darkened. Then it cleared, and I saw as distinctly as I ever saw anything in my life—I saw, I say, our boat upon that horrible canal. There was Leo lying at the bottom asleep in it, with a coat thrown over him to keep off the mosquitoes, in such a fashion as to hide his face, and myself, Job, and Mahomed towing on the bank.

and Imhotep puts a pool to similar purpose. ![[screen-shot of Imhotep before the viewing pool]](wp-content/uploads/2009/06/viewpool.jpg) There are even occasional lines of dialogue in The Mummy (1932) that are essentially lifted from She:

There are even occasional lines of dialogue in The Mummy (1932) that are essentially lifted from She:

| She | The Mummy |

|---|

Shall I raise thee, she said, apparently addressing the corpse, so that thou standest there before me, as of old? I can do it, and she held out her hands over the sheeted dead, while her whole frame became rigid and terrible to see, and her eyes grew fixed and dull. I shrank in horror behind the curtain, my hair stood up upon my head, and, whether it was my imagination or a fact I am unable to say, but I thought that the quiet form beneath the covering began to quiver, and the winding sheet to lift as though it lay on the breast of one who slept. Suddenly she withdrew her hands, and the motion of the corpse seemed to me to cease.

To what purpose? she said gloomily. Of what good is it to recall the semblance of life when I cannot recall the spirit? Even if thou stoodest before me thou wouldst not know me, and couldst but do what I bid thee. The life in thee would be my life, and not thy life, Kallikrates.

| Imhotep: It is thy dead shell. I tried then to raise this body; I could raise it now. But it would be only a thing that moved at my will, without a soul. Imhotep: It was not only this body that I loved; it was thy soul. |

Once Ayesha feels secure that Kallikrates is restored to her in another body, she pours a mysterious fluid on the prior, preserved body and reduces it to smoke and ash. Once Imhotep feels secure that Anck-es-en-Amon is restored to him in another body, he sets her prior, mummified body afire. (I destroy this lifeless thing.

)

The parallels are not mysterious. John L. Balderston, who wrote the screen-play for The Mummy (starting with a story by Nina Wilcox Putnam and Richard Schayer but changing it from a science-fantasy about a serial killer who maintained an existence through the centuries), was in-process also assigned by Universal Studios to adapt She.[1][2]

But there's a very great departure with The Mummy — greater than the reversal of sexes.

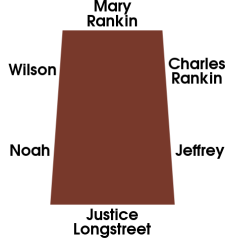

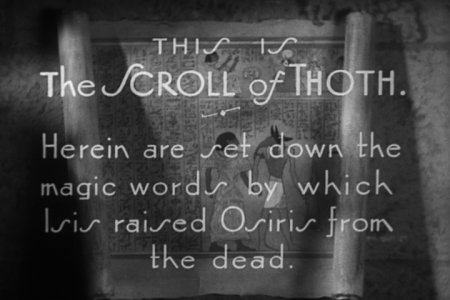

Imhotep is dead. He is dead when he is found in the sarcophagus; he is reänimated by a scroll,[3]

but it is something that only works upon the dead, and does not restore true life.

Balderston's script, Pierce's make-up and Karloff's

incredible performance convey that Imhotep is

dry and

stiff. The dialogue is quite explicit:

Dr Muller: If I could get my hands on you, I'd break your dried flesh to pieces.

and there's the terrible moment in which Anck-es-en-Amon

recognizes that Imhotep is dead:

Ayesha, on the other hand, may be about 2000 years old, but she is utterly alive.

Though the face before me was that of a young woman of certainly not more than thirty years, in perfect health, and the first flush of ripened beauty, yet it had stamped upon it a look of unutterable experience, and of deep acquaintance with grief and passion. Not even the lovely smile that crept about the dimples of her mouth could hide this shadow of sin and sorrow. It shone even in the light of the glorious eyes, it was present in the air of majesty, and it seemed to say: Behold me, lovely as no woman was or is, undying and half-divine; memory haunts me from age to age, and passion leads me by the hand — evil have I done, and from age to age evil I shall do, and sorrow shall I know till my redemption comes.

She has never died, having bathed in a column of pure life energy.

We stood in a third cavern, some fifty feet in length by perhaps as great a height, and thirty wide. It was carpeted with fine white sand, and its walls had been worn smooth by the action of I know not what. The cavern was not dark like the others, it was filled with a soft glow of rose-coloured light, more beautiful to look on than anything that can be conceived. But at first we saw no flashes, and heard no more of the thunderous sound. Presently, however, as we stood in amaze, gazing at the marvellous sight, and wondering whence the rosy radiance flowed, a dread and beautiful thing happened. Across the far end of the cavern, with a grinding and crashing noise — a noise so dreadful and awe-inspiring that we all trembled, and Job actually sank to his knees — there flamed out an awful cloud or pillar of fire, like a rainbow many-coloured, and like the lightning bright. For a space, perhaps forty seconds, it flamed and roared thus, turning slowly round and round, and then by degrees the terrible noise ceased, and with the fire it passed away — I know not where — leaving behind it the same rosy glow that we had first seen.

Draw near, draw near!

cried Ayesha, with a voice of thrilling exultation. Behold the very Fountain and Heart of Life as it beats in the bosom of the great world. Behold the substance from which all things draw their energy, the bright Spirit of the Globe, without which it cannot live, but must grow cold and dead as the dead moon. Draw near, and wash you in the living flames, and take their virtue into your poor frames in all its virgin strength — not as it now feebly glows within your bosoms, filtered thereto through all the fine strainers of a thousand intermediate lives, but as it is here in the very fount and seat of earthly Being.

We followed her through the rosy glow up to the head of the cave, till at last we stood before the spot where the great pulse beat and the great flame passed. And as we went we became sensible of a wild and splendid exhilaration, of a glorious sense of such a fierce intensity of Life that the most buoyant moments of our strength seemed flat and tame and feeble beside it. It was the mere effluvium of the flame, the subtle ether that it cast off as it passed, working on us, and making us feel strong as giants and swift as eagles.

We reached the head of the cave, and gazed at each other in the glorious glow, and laughed aloud — even Job laughed, and he had not laughed for a week — in the lightness of our hearts and the divine intoxication of our brains. I know that I felt as though all the varied genius of which the human intellect is capable had descended upon me. I could have spoken in blank verse of Shakesperian beauty, all sorts of great ideas flashed through my mind; it was as though the bonds of my flesh had been loosened and left the spirit free to soar to the empyrean of its native power. The sensations that poured in upon me are indescribable. I seemed to live more keenly, to reach to a higher joy, and sip the goblet of a subtler thought than ever it had been my lot to do before. I was another and most glorified self, and all the avenues of the Possible were for a space laid open to the footsteps of the Real.

Then, suddenly, whilst I rejoiced in this splendid vigour of a new-found self, from far, far away there came a dreadful muttering noise, that grew and grew to a crash and a roar, which combined in itself all that is terrible and yet splendid in the possibilities of sound. Nearer it came, and nearer yet, till it was close upon us, rolling down like all the thunder-wheels of heaven behind the horses of the lightning. On it came, and with it came the glorious blinding cloud of many-coloured light, and stood before us for a space, turning, as it seemed to us, slowly round and round, and then, accompanied by its attendant pomp of sound, passed away I know not whither.

For Kallikrates/Leo to be joined with Ayesha, he must bathe in this Flame of Life as she once did. Holly's narrative makes it plain that to be in the presence of the column is thrilling, and causes him to throw-off his former rejection of the near immortality that it would bestow.

And that will I also,

I cried.

What, my Holly!

she laughed aloud; methought that thou wouldst naught of length of days. Why, how is this?

Nay, I know not,

I answered, but there is that in my heart that calleth me to taste of the flame and live.

Leo has been promised that he will not be harmed: It is not wonderful that thou shouldst doubt. Tell me, Kallikrates: if thou seest me stand in the flame and come forth unharmed, wilt thou enter also?

[4]

On the other hand, Anck-es-en-Amon/Helen has been taken to a place of embalming, and informed that she must be killed and mummified to be joined with Imhotep. Upon setting her prior body alight, Imhotep had promised her Thou shall take its place but for a few moments. And then … rise again even as I have risen.

When Time catches-up to Ayesha, it is to age her:

As soon as it was gone, she stepped forward to Leo's side — it seemed to me that there was no spring in her step — and stretched out her hand to lay it on his shoulder. I gazed at her arm. Where was its wonderful roundness and beauty? It was getting thin and angular. And her face — by Heaven! — her face was growing old before my eyes! I suppose that Leo saw it also; certainly he recoiled a step or two.

[…] She was dying: we saw it, and thanked God — for while she lived she could feel, and what must she have felt? She raised herself upon her bony hands, and blindly gazed around her, swaying her head slowly from side to side as a tortoise does. She could not see, for her whitish eyes were covered with a horny film. Oh, the horrible pathos of the sight! But she could still speak.

[…] On the very spot where more than twenty centuries before she had slain Kallikrates the priest, she herself fell down and died.

When it catches up to Imhotep, it is to reduce his body to bones and dust:

The Mummy ends with Time catching-up to an old corpse; but She climaxed with Time catching-up to an old woman. At no point in She is Ayesha mummified or anything much like that. What is left behind in the cavern is the body of a very agèd, hairless, shrunken woman.

In fairness to Broadview Press, I note that the cover image is of the mummified corpse of Neskhons, which had attracted Haggard's interest, albeït after Haggard had completed a draft of She.

[1] There had been six prior movie adaptations of She. In the end, Universal did not produce a version, and ultimately sold its rights to RKO Pictures. The script for the 1935 version from RKO was badly written by Ruth Rose (with some additional dialogue by Dudley Nichols).

[2] Paul M. Jensen, in his commentary to The Mummy for the 2004 release, eventually touches upon the relationship of The Mummy to She, but makes confused misstatements about Haggard's story in the latter.

[3] In The Mummy's Hand (1940), the titular mummy had instead been kept alive for centuries by a potion brewed from tanna leaves. This movie makes other radical changes and, though it reüses footage and significant elements from the earlier film, doesn't represent a continuation of nor prequel to the story in The Mummy.

[4] Jensen asserts Before Ayesha can be reunited with her reincarnated love, he must die and be reborn, thus becoming immortal like her.

Plainly, he is in error.

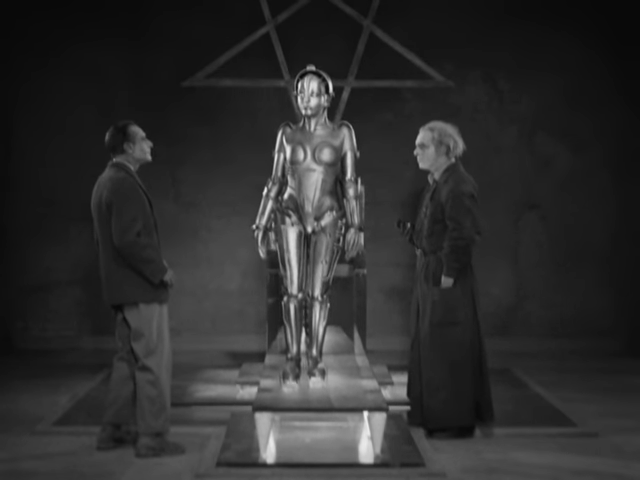

and for its depiction of a city of great skyscrapers, elevated roadways, and aircraft.

and for its depiction of a city of great skyscrapers, elevated roadways, and aircraft.  Others will remember it for what they take to be a humanistic message about the relationship between physical laborers and thought-workers being brought and kept into harmonious relations by kindness. The ideologic subtext is often unrecognized.

Others will remember it for what they take to be a humanistic message about the relationship between physical laborers and thought-workers being brought and kept into harmonious relations by kindness. The ideologic subtext is often unrecognized. At the least, this institution controls power production and water delivery. The institution seems to employ the entirety or nearly the entirety of a substantial proletariat, living and working underground.

At the least, this institution controls power production and water delivery. The institution seems to employ the entirety or nearly the entirety of a substantial proletariat, living and working underground.  The institution can act as a state in response to a violent uprising by this proletariat. Moreover, the head of the institution, Joh[ann] Frederson,

The institution can act as a state in response to a violent uprising by this proletariat. Moreover, the head of the institution, Joh[ann] Frederson,  is said to be responsible for the city more generally.

is said to be responsible for the city more generally. their living conditions impoverished. But the proletariat are lacking in intelligence and self-control. When one, Georgy 11811, is rescued by Freder (son of Johann Frederson) from labor that is overwhelming Georgy,

their living conditions impoverished. But the proletariat are lacking in intelligence and self-control. When one, Georgy 11811, is rescued by Freder (son of Johann Frederson) from labor that is overwhelming Georgy, and tasked by Freder with going to an apartment to meet with him later, Georgy instead takes money left in his care and goes to the pleasure district,

and tasked by Freder with going to an apartment to meet with him later, Georgy instead takes money left in his care and goes to the pleasure district,  even as his savior suffers in place of Georgy.

even as his savior suffers in place of Georgy.  (Freder's other disciple, drawn from the managerial class, is unfailingly faithful.) Later, with just the one exception of a foreman, each and every man and woman in the underground allow themselves to be persuaded to destroy the machinery running the city, and then thoughtlessly monkey-dance in the ruins

(Freder's other disciple, drawn from the managerial class, is unfailingly faithful.) Later, with just the one exception of a foreman, each and every man and woman in the underground allow themselves to be persuaded to destroy the machinery running the city, and then thoughtlessly monkey-dance in the ruins  even as their children face drowning when water from the reservoir comes flooding into the residential area. Plainly, one wants no dictatorship of this proletariat, nor to have them make any decisions of import.

even as their children face drowning when water from the reservoir comes flooding into the residential area. Plainly, one wants no dictatorship of this proletariat, nor to have them make any decisions of import.

![[Still image showing portrait of Laura Hunt in background]](wp-content/uploads/2010/07/laura_portrait_450x300.jpg)

![[Marguerite, suddenly reälizing who the Scarlet Pimpernel is]](http://www.oeconomist.com/blogs/daniel/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/marguerite_1.jpg) where pieces all click together in the mind of one of the characters, revealing something important.

where pieces all click together in the mind of one of the characters, revealing something important.![[Marguerite, overtly reäcting to the reälization]](http://www.oeconomist.com/blogs/daniel/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/marguerite_2.jpg) As she looks again at the painting, her mouth is asymmetrical as she moves towards laughter

As she looks again at the painting, her mouth is asymmetrical as she moves towards laughter ![[Marguerite, almost laughing]](http://www.oeconomist.com/blogs/daniel/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/marguerite_3.jpg) at the deception Percy has effected. But the joke is displaced in her mind and her expression moves towards a smile of a different, symmetric sort

at the deception Percy has effected. But the joke is displaced in her mind and her expression moves towards a smile of a different, symmetric sort ![[Marguerite, almost smiling]](http://www.oeconomist.com/blogs/daniel/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/marguerite_4.jpg) as she starts to think that her Percy is a better man than she had come to think him, and indeed a better man than she had thought him when they married. She doesn't get very far with that thought, as it hits her

as she starts to think that her Percy is a better man than she had come to think him, and indeed a better man than she had thought him when they married. She doesn't get very far with that thought, as it hits her ![[Marguerite, seized with fear and with grief]](http://www.oeconomist.com/blogs/daniel/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/marguerite_5.jpg) that Percy has sailed off not only into danger but into danger that she has caused to be greatly increased.

that Percy has sailed off not only into danger but into danger that she has caused to be greatly increased.![[image of a mummified woman]](wp-content/uploads/2009/06/She_Broadview.jpg) is interesting, in large part because it is almost perfectly wrong. I'll explain what's wrong with the use of the image of this mummy by comparing and contrasting

is interesting, in large part because it is almost perfectly wrong. I'll explain what's wrong with the use of the image of this mummy by comparing and contrasting ![[screen-shot of Imhotep before the viewing pool]](wp-content/uploads/2009/06/viewpool.jpg) There are even occasional lines of dialogue in

There are even occasional lines of dialogue in

Balderston's script, Pierce's make-up and Karloff's incredible performance convey that Imhotep is dry and stiff. The dialogue is quite explicit:

Balderston's script, Pierce's make-up and Karloff's incredible performance convey that Imhotep is dry and stiff. The dialogue is quite explicit: