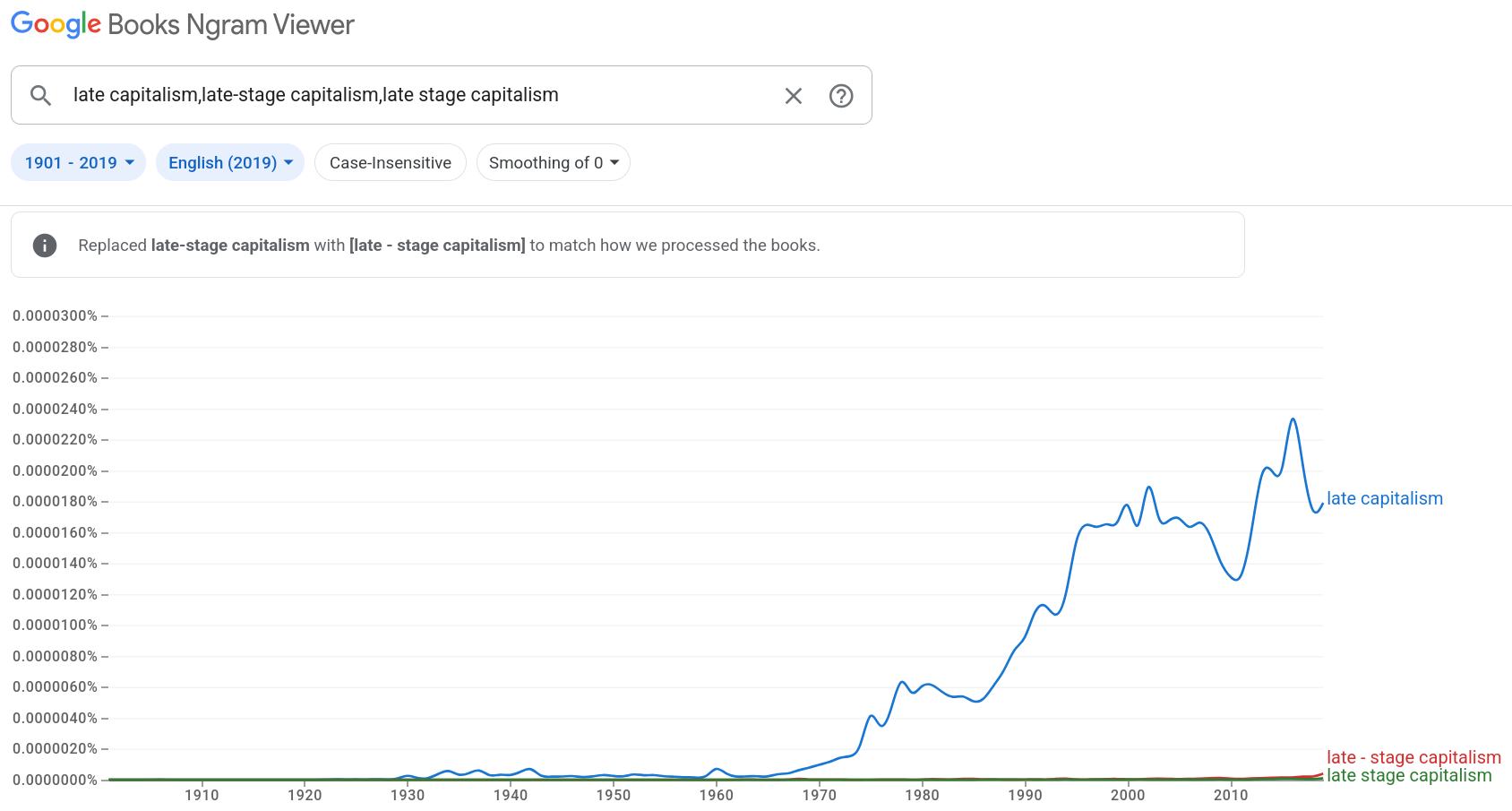

Measures — quantities to which some arithmetic can be meaningfully applied — can be fitted to some human attributes, even if not to others. When attempting to compare some populations to others, an assumption is made that the properties of the individuals within these populations are subject to quantification of some sort, and that the quantities are commensurable across populations. But usually these assumptions are implicit and unrecognized, and even those who have some awareness that they are dealing with quantities very often don't have a proper grasp of elementary issues.

Very often, people try to understand distinct populations in terms of some notion of averages. If each and every member of every population were exactly average in every regard, then averages would be perfect measures of the populations as such. More generally, if for any two populations the share of that population deviating from average by some specific amount were the same, averages would be sufficient for any comparison of the attributes of populations, except for population sizes. But if the overall variance from average in one population is different from that in another, then thinking in terms of averages can go very, very wrong.

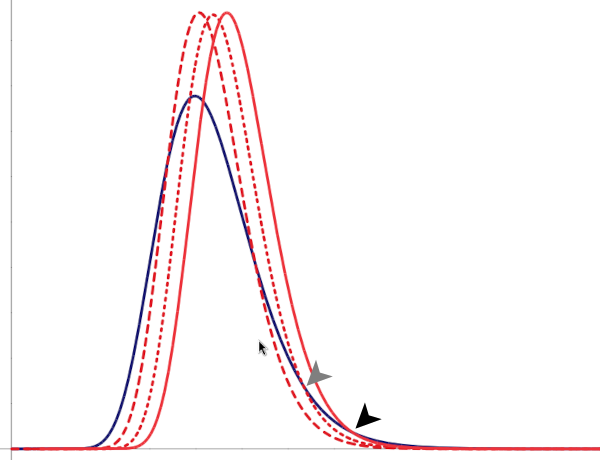

Here are hypothetic distributions for some attribute within two populations, each population having the same number of members:[1] ![[two lognormal distributions of equal median but of different variance]](wp-content/uploads/2024/08/equal_median_0.png) For both Population A and Population B, the median[2] of the attribute is the same, but Population B has more variance from the arithmetic mean than does Population A. Even though each of these two populations have the same median, more members of the population of greater variance are below some some measure, and more members of that same population are above some measure.

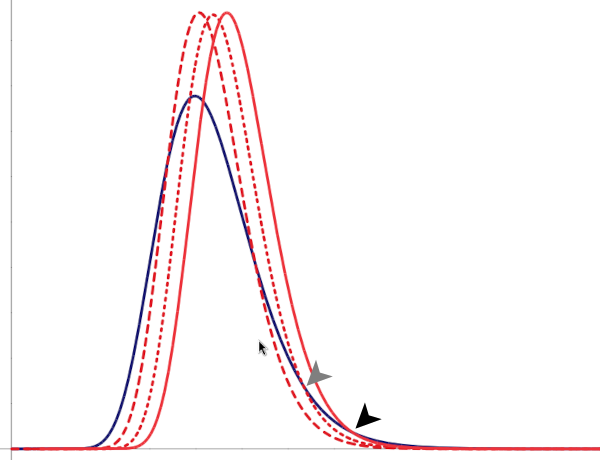

For both Population A and Population B, the median[2] of the attribute is the same, but Population B has more variance from the arithmetic mean than does Population A. Even though each of these two populations have the same median, more members of the population of greater variance are below some some measure, and more members of that same population are above some measure. ![[two lognormal distributions of equal median but of different variance]](wp-content/uploads/2024/08/equal_median_1.png) Population B2

Population B2 ![[two lognormal distributions of equal mean but of different variance]](wp-content/uploads/2024/08/equal_mean_1.png) has the same variance as Population B, but the same arithmetic mean (rather than median) as Population A. Again, even though the center is, by some measure, the same for both populations, more members of the population of greater variance are below some some measure, and more members of that same population are above some measure.

has the same variance as Population B, but the same arithmetic mean (rather than median) as Population A. Again, even though the center is, by some measure, the same for both populations, more members of the population of greater variance are below some some measure, and more members of that same population are above some measure.

Even if a population has a higher center than Population A, if it has a greater variance then it will dominate the lower range of measures below some measure. ![[two lognormal distributions of different mean and variance]](wp-content/uploads/2024/08/higher_center.png) And even if a population has a lower center than Population A, if it has a greater variance then it will dominate the higher range of measures beyond some measure.

And even if a population has a lower center than Population A, if it has a greater variance then it will dominate the higher range of measures beyond some measure. ![[two lognormal distributions of different mean and variance]](wp-content/uploads/2024/08/lower_center.png)

If a measurable attribute correlates positively with social success, then ceteris paribus, a population of higher variance is going to dominate both social winners beyond some level and social losers below some level. If a population generally has greater variance amongst its attributes, then — discarding the assumption of ceteris paribus — that population is going to dominate both social winners beyond some level and social losers below some level; even if it has the same median or same mean or even a lower center than another populations.

In fact, though I cannot readily graph the cases in which attributes are only partially ordered and not measurable, the reader should see that the underlying point does not depend upon the measurability of the attributes, but only upon one population having greater propensity for variance than another.

But

- If one is only looking at the losers and thoughtlessly assuming that their numbers are explained by averages, then one is going inappropriately to infer that the population is generically inferior.

- If one is only looking at the losers, while thoughtlessly assuming that the averages are the same and that nothing else about the population itself can explain the difference in outcomes, then one is going inappropriately to infer that the population are victims of systemic bias.

- If one is only looking at the winners and thoughtlessly assuming that their numbers are explained by averages, then one is going inappropriately to infer that the population is generically superior.

- If one is only looking at the winners, while thoughtlessly assuming that the averages are the same and that nothing else about the population itself can explain the difference in outcomes, then one is going inappropriately to infer that any rival population are victims of systemic bias.

In each case, if we look at the other end of the distribution, the thoughtless conclusion falls apart.

When the last of these errors is made, an attempt may be undertaken to offset illusory bias, by putting an institutional thumb on the scales to shift Population A generally forward, until the the number of social winners at every level is at least the same. But notice what is then really happening  as the relative outcomes for most members of the population of greater variance fall increasingly below those of the population of less variance — at previously targetted levels the population of lower variance comes to enjoy greater social success than does the population of greater variance. And notice that the population of greater variance necessarily still dominates above some value, albeït that the value increases as the institutional thumb comes down ever harder in a misguided attempt to match the upper tails of the distribution.

as the relative outcomes for most members of the population of greater variance fall increasingly below those of the population of less variance — at previously targetted levels the population of lower variance comes to enjoy greater social success than does the population of greater variance. And notice that the population of greater variance necessarily still dominates above some value, albeït that the value increases as the institutional thumb comes down ever harder in a misguided attempt to match the upper tails of the distribution.

Only actual systemic bias can bring the number of social winners across populations into equality above any given level of social success beyond the center; and, the larger the population, the greater the required bias for such an outcome, and the more that most of the population of greater variance are victimized.

If the two populations are not equal in size, then the foregoing analysis would simply need to entail talk of proportionality. But one might as well speak and write of two populations of the same size, because the real-world application involves two populations that are very close to the same size in most first-world nations. The greater variance of one of those two populations is a consequence of the greater chaos in the formation of one of that population's chromosomes and of a lack of redunancy for another.

Unfortunately, most of the attempts to analyze what has been happening has entailed ham-fisted theorizing about differing averages.

[1] A population with finite membership cannot perfectly conform to a continuous distribution function; but, the larger the population, the less the necessary non-conformance.

[2] The median for each population is the point such that as many members of the population are above it as are below it.

![[image of mathematic formula]](wp-content/uploads/2024/09/AP11.png) This refactoring is mathematically trivial, exploiting two automorphisms, but exhibits the principle more elegantly.

This refactoring is mathematically trivial, exploiting two automorphisms, but exhibits the principle more elegantly.![[image of mathematic formula]](wp-content/uploads/2024/08/A9.png) may be more simply stated as

may be more simply stated as ![[image of mathematic formula]](wp-content/uploads/2024/08/AP7.png)

![[two lognormal distributions of equal median but of different variance]](wp-content/uploads/2024/08/equal_median_0.png) For both Population A and Population B, the median

For both Population A and Population B, the median![[two lognormal distributions of equal median but of different variance]](wp-content/uploads/2024/08/equal_median_1.png) Population B2

Population B2 ![[two lognormal distributions of equal mean but of different variance]](wp-content/uploads/2024/08/equal_mean_1.png) has the same variance as Population B, but the same arithmetic mean (rather than median) as Population A. Again, even though the center is, by some measure, the same for both populations, more members of the population of greater variance are below some some measure, and more members of that same population are above some measure.

has the same variance as Population B, but the same arithmetic mean (rather than median) as Population A. Again, even though the center is, by some measure, the same for both populations, more members of the population of greater variance are below some some measure, and more members of that same population are above some measure.![[two lognormal distributions of different mean and variance]](wp-content/uploads/2024/08/higher_center.png) And even if a population has a lower center than Population A, if it has a greater variance then it will dominate the higher range of measures beyond some measure.

And even if a population has a lower center than Population A, if it has a greater variance then it will dominate the higher range of measures beyond some measure. ![[two lognormal distributions of different mean and variance]](wp-content/uploads/2024/08/lower_center.png)

as the relative outcomes for most members of the population of greater variance fall increasingly below those of the population of less variance — at previously targetted levels the population of lower variance comes to enjoy greater social success than does the population of greater variance. And notice that the population of greater variance necessarily still dominates above some value, albeït that the value increases as the institutional thumb comes down ever harder in a misguided attempt to match the upper tails of the distribution.

as the relative outcomes for most members of the population of greater variance fall increasingly below those of the population of less variance — at previously targetted levels the population of lower variance comes to enjoy greater social success than does the population of greater variance. And notice that the population of greater variance necessarily still dominates above some value, albeït that the value increases as the institutional thumb comes down ever harder in a misguided attempt to match the upper tails of the distribution.

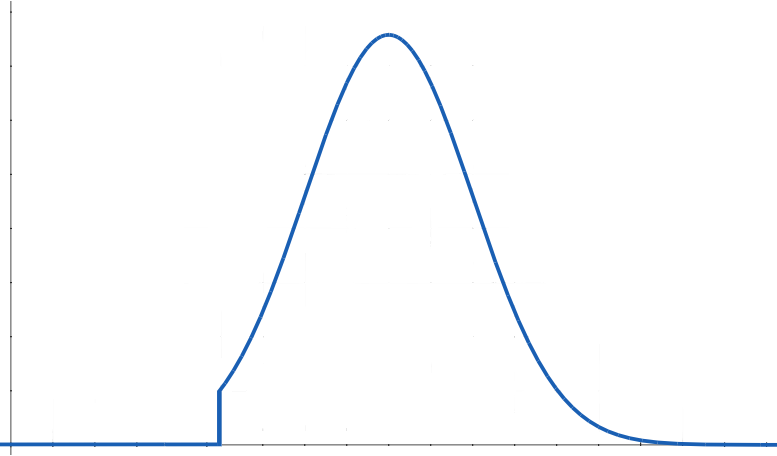

usually doesn't make a great deal of sense, because few people will even be near the lower bound, rather than a fair number at it or just barely above it.

usually doesn't make a great deal of sense, because few people will even be near the lower bound, rather than a fair number at it or just barely above it.