and no sound came back of his going

Monday, 13 July 2009

Some weeks ago, I mentioned to the Woman of Interest my having looked, as a child, for rôle models in fictional heroes. She made the natural but mistaken inference that the Batman would have been amongst these. As I explained to her, when I was of such an age to look, the Batman was still morphed into Batman, a scientific detective who wore a bat suit for no particularly good reason; it was only later that Denny O'Neil brought back the Batman.[1] A character whom I then mentioned was Robert E. Howard's Solomon Kane. My father had a copy of Red Shadows, published by Donald M. Grant, which collected a number of stories about Kane.[2] Kane, a wandering English Puritan, believes that, when he comes upon injustice, it is his obligation to set things as right as they might be. Although he is a tool that can be broken, he is none-the-less an instrument of G_d's justice. Howard described Kane as a fanatic

.[3] Curious, the Woman of Interest located The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane, a more recent collection.[4]

As I'd not anticipated her doing this, I hadn't mentioned to her that I'd liked the earliest stories a great deal, but the later stories far less. Frankly, I didn't and don't necessarily remember all these reasons for that opinion of my childhood. But, in any case, she likewise didn't like the later stories. More specifically, she was unhappy with the racism that began to surface in them, clearly with The Moon of Skulls

.

Partly in response to her reäction, and partly because I recalled The Moon of Skulls

as having thematic elements that I now recognize as drawn from Haggard's She and wanted to examine as such, I decided to get a copy of The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane and re-read the stories.

Howard's racialism was not that of, say, Lovecraft. Howard's characters include black heroes as well as black villains. One black character, N'Longa, who seems sly and amoral or wicked in Red Shadows

(originally Solomon Kane

), is later developed in The Hills of the Dead

as profoundly wise and on the side of the good. None-the-less, blacks are treated as, in general, less able people, as if intrinsically so.

The work seemed very old and very much superior to what might be expected of a tribe of ignorant negroes.

[…]

The black people who thronged that mighty room seemed grotesquely incongruous. They no more suited their surroundings than a band of monkeys would have seemed at home in the council chambers of the English king.[5]

And notion of intrinsic inferiority is unmistakeably present in the comparison of subtypes.

The girl was a much higher type than the thick-lipped, bestial West Coast negroes to whom Kane had been used. She was slim and finely formed, of a deep brown hue rather than ebony; her nose was straight and thin-bridged, her lips were not too thick. Somewhere in her blood there was a strong Berber strain.[6]

Meanwhile, the notion of Kane as somehow superior because he is Anglo-Saxon, because he is white, because he is Aryan becomes a recurring theme.

Kane stood, an unconscious statue of triumph — the ancient empires fall, the dark-skinned peoples fade and even the demons of antiquity gasp their last, but over all stands the Aryan barbarian, white-skinned, cold-eyed, dominant, the supreme fighting man of the earth, whether he be clad in wolf-hide and horned helmet, or boots and doublet — whether he bear in his hand battle-ax or rapier — whether he be called Dorian, Saxon, or Englishman — whether his name be Jason, Hengist or Solomon Kane.[7]

The scary references to Aryan barbarians not-with-standing, Howard's racialism wasn't hate-filled. He was appalled by the Italian bombing of Ethiopia, and it's interesting to think what he might have learned had he lived into the post-war era, instead of blowing his brains out in 1936. His racialism strikes me as an expression of a combination of ignorance and of a childish longing for every-day magic. Howard had no formal education in the social or biological sciences beyond high school, and would have been informed by popularizations such as the Little Blue Books. At different points, he got enthusiastic about different ethnic groups — with later Solomon Kane stories, it's the Germanic conquerors of what became England; with other stories it's the very Celts whom they'd conquered.

I cannot tell you what my personal reäction as a child had been to the racism here. At that age, I read a lot of reprinted pulp fiction[8] from the inter-war period, and there's racism of various sorts and intensities in that stuff. I knew that the racism was rubbish, but I simply don't remember whether my response were to wince or to treat it as any other mythology.

What certainly put me off was Howard transforming Kane, from someone driven primarily by his pursuit of justice, into someone who'd felt some sort of call to travel across Africa, west-to-east; from an relentless avenger to a barbarian mixing it up mostly just because this, in Howard's mythologies, is what barbarians spend their time doing. I've never been able to work-up much enthusiasm for Conans or for Kulls.

Howard once listed Haggard amongst his favorite authors, and Haggard's influence on fantasy and adventure fiction are such that, in any event, one should not be surprised at seeing elements of She in The Moon of Skulls

.

Both depict cities, each built by a pre-Egyptian civilization, hidden in the interior of Africa, now inhabited by dark-skinned savages, and ruled by a beautiful tyrant queen. The savage inhabitants make a habit of killing any who come into their land (though those in Howard's story will apparently make an exception for those who bear tribute). Haggard's Ayesha has foreseen the coming of white men, and ordered that they be brought to her unharmed; when an attempt is made to subvert and then violate this directive, she has the perpetrators horribly tortured to death. Howard's Nakari only learns of the arrival of a white man after her guards believe that they have killed him, but she is frustrated at word of his death and has the captain of the guards killed. Ayesha is about 2000 years old, and as near to immortal as one might be. Though the reference is unexplained, Nakari is called the vampire queen

of the city in The Moon of Skulls

, and is almost surely of her whom Kane speaks in Howard's poem Solomon Kane's Homecoming

when he says

“And I have known a deathless queen / in a city as old as Death,[9]

Each queen derives her power from secrets pried from the last possessors of the secrets of the ancient people who built of their respective cities. Ayesha plans on world-domination once Leo is at her side. Meeting Kane, Nakari begins to dream of world conquest with him at hers. Ayesha is venomously jealous in reäction to Leo's concern for one of her subjects, Ustane,[10] while Nakari is venomous and jealous in reäction to Kane's concern for the slave-girl Mara.

However, Ayesha and Nakari are also markèdly different, in appearance and in character. Ayesha is an Arab with skin white as snow

.

At length the curtain began to move. Who could be behind it? — some naked savage queen, a languishing Oriental beauty, or a nineteenth-century young lady, drinking afternoon tea? I had not the slightest idea, and should not have been astonished at seeing any of the three. I was getting beyond astonishment. The curtain agitated itself a little, then suddenly between its folds there appeared a most beautiful white hand (white as snow), and with long tapering fingers, ending in the pinkest nails. The hand grasped the curtain, and drew it aside, and as it did so I heard a voice, I think the softest and yet most silvery voice I ever heard. It reminded me of the murmur of a brook.

[…]

Though the face before me was that of a young woman of certainly not more than thirty years, in perfect health, and the first flush of ripened beauty, yet it had stamped upon it a look of unutterable experience, and of deep acquaintance with grief and passion. Not even the lovely smile that crept about the dimples of her mouth could hide this shadow of sin and sorrow. It shone even in the light of the glorious eyes, it was present in the air of majesty, and it seemed to say:Behold me, lovely as no woman was or is, undying and half-divine; memory haunts me from age to age, and passion leads me by the hand — evil have I done, and from age to age evil I shall do, and sorrow shall I know till my redemption comes.

But Nakari is, indeed, pretty much some naked savage queen

.

A black woman she was, young and of tigerish comeliness. She was naked except for a beplumed helmet, armbands, anklets and a girdle of colored ostrich feathers, and she sprawled upon the silken cushions with her limb thrown about in voluptuous abandon.

Even at that distance Kane could make out that her features were regal yet barbaric, haughty and imperious, yet sensual, and with a touch of ruthless cruelty about the curl of her full red lips.

Haggard's Ayesha used her feminine charm to gain her near-immortality.

I heard of this philosopher, and waited for him when he came to fetch his food, and returned with him hither, though greatly did I fear to tread the gulf. Then did I beguile him with my beauty and my wit, and flatter him with my tongue, so that he led me down and showed me the Fire, and told me the secrets of the Fire, but he would not suffer me to step therein, and, fearing lest he should slay me, I refrained, knowing that the man was very old, and soon would die.

Howard's Nakari, went about things in a less winning manner, and what she has learned is mummery, rather than magic.

Listen, white man,the shackled one spoke with strange solemnity;I am dying. Nakari's rack has done its work. I die and with me dies the shadow of the glory that was my nation's. For I am the last of my race. In all the world there is none like me. Hark now, to the voice of a dying race.

[…]As a child, she danced in the March of the New Moon, and as a young girl she was one of the Star-maidens. Much of the lesser mysteries was known to her, and more she learned, spying on the secret rites of the priests who enacted hidden rituals that were old when the earth was young. […] She alone of all the myriad black thousands who have lived and died between these walls guessed at the hidden passages and subterranean corridors, secrets which we of the priestcraft had guarded jealously from the people for a thousand years.

[…]Torture could not wring these secrets from our lips, but shackled in her dungeons, we trod our hidden corridors no more. [….]

[…]But Nakari discovered the secret, known before only to the brown priests, and now one of her Satellites mounts the hidden stair and yammers forth the strange and terrible chant which is but meaningless gibberish to him, as to those who hear it. [….]

Ayesha is cruel, deadly, and given to bursts of fury, but takes no sadistic delight in the hurt that she causes. When Holly pleads for mercy for those who had tried to kill his party, She replies

My Holly, it cannot be. Were I to show mercy to those wolves, your lives would not be safe among this people for a day. Thou knowest them not. They are tigers to lap blood, and even now they hunger for your lives. How thinkest thou that I rule this people? I have but a regiment of guards to do my bidding, therefore it is not by force. It is by terror. My empire is of the imagination. Once in a generation mayhap I do as I have done but now, and slay a score by torture. Believe not that I would be cruel, or take vengeance on anything so low. What can it profit me to be avenged on such as these? Those who live long, my Holly, have no passions, save where they have interests. Though I may seem to slay in wrath, or because my mood is crossed, it is not so. Thou hast seen how in the heavens the little clouds blow this way and that without a cause, yet behind them is the great wind sweeping on its path whither it listeth. So it is with me, oh Holly. My moods and changes are the little clouds, and fitfully these seem to turn; but behind them ever blows the great wind of my purpose. Nay, the men must die; and die as I have said.

But Nakari is plainly the sadist. When Kane rejects Nakari and demands to be released with Mara, Nakari thinks to kill him in her rage, but then says

Freedom? She will find her freedom when the Moon of Skulls leers down on the black altar. As for you, you shall rot in this dungeon. Your are a fool; Africa's greatest queen has offered you her love and the empire of the world — and you revile her! You love the white girl, perhaps? Until the Moon of Skulls she is mine and I leave you to think about this: that she shall be punished as I have punished her before — hung up by her wrists, naked, and whipped until she swoons!

In her embodiment of sin, Nakari may be closer to Haggard's original vision of Ayesha. Haggard set-out to write a story of an evil sorceress driven by an obsessive love. But the author himself was won-over by that love, and Ayesha transformed. Nothing redeems Nakari.

The illustrations for Red Shadows were done by Jeff Jones, one of the outstanding illustrators of the last few decades. Those for The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane were done by Gary Gianni. Gianni has, in fact, acquitted himself quite well. The interior pen-and-ink illustrations are outstanding, and reminiscent of some of the fine illustrations that used to be more common in books of adventure fiction.[11] The paintings are not as successful, but would simply seem satisfactory if only they weren't in proximity to drawings of such merit.

[1] The notion that it were Frank Miller who returned the Batman to his dark roots is simply ignorant.

[2] My understanding is that it contains all of the Kane material except the fragment Death's Black Riders

.

[3] Years later, as O'Neil was embarking on his restoration of the Batman, I heard him speak at Fairleigh Dickinson University, and he used the same word, fanatic

, to describe his notion of the Batman.

[4] Which collection includes Death's Black Riders

.

[5] The Moon of Skulls

.

[6] The Hills of the Dead

. Though, again, it is in this same story that N'Longa's wisdom and goodness is revealed below his surface.

[7] Wings in the Night

. The references to the demons of antiquity

and to Jason are because Kane had just destroyed the last of the harpies, whom Ιασων had apparently driven from Europe into Africa. Kane manages to single-handedly destroy the harpies after the harpies have gruesomely exterminated two entire villages of hapless blacks.

[8] When I refer to pulps

and to pulp fiction

, I'm not referring to the cheap paper-back books of the post-war era. A pulp was a sort of perfect-bound magazine of fiction, typically about 7in (18cm) × 10in (25cm), printed on cheap pulp paper. Some of these have continued into the present, though in changed format; for example, Astounding is now Analog. The real relationship between these pulps and the cheap paper-back books that appeared later is that those books both reprinted stories from the pulps and were a rival market for new work.

[9] The poem continues

“Where towering pyramids of skulls / her glory witnesseth.

“Her kiss was like an adder's fang, / with the sweetness Lilith had,

“And her red-eyed vassals howled for blood / in that City of the Mad.

and, at the climax of The Moon of Skulls

, the inhabitants are indeed gone mad with lust for killing.

[10] For the love of G_d, Ustane

would be pronounced /usˈtane/, not /usˈten/.

[11] There is a slip in the next-to-last illustration for part I of The Children of Asshur

. Gianni has drawn Kane with a sword and scabbard, in a fight in which he was armed with only an axe.

![[image of a mummified woman]](wp-content/uploads/2009/06/She_Broadview.jpg) is interesting, in large part because it is almost perfectly wrong. I'll explain what's wrong with the use of the image of this mummy by comparing and contrasting

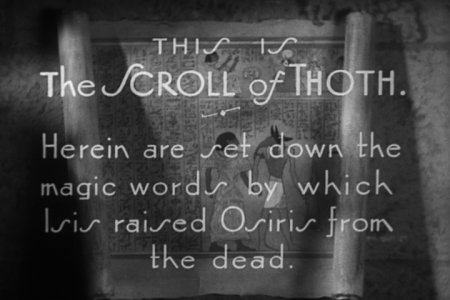

is interesting, in large part because it is almost perfectly wrong. I'll explain what's wrong with the use of the image of this mummy by comparing and contrasting ![[screen-shot of Imhotep before the viewing pool]](wp-content/uploads/2009/06/viewpool.jpg) There are even occasional lines of dialogue in

There are even occasional lines of dialogue in

Balderston's script, Pierce's make-up and Karloff's incredible performance convey that Imhotep is dry and stiff. The dialogue is quite explicit:

Balderston's script, Pierce's make-up and Karloff's incredible performance convey that Imhotep is dry and stiff. The dialogue is quite explicit: