Everyday discussions of epistemics don't require us to discuss foundational epistemology explicitly. Were someone asked how she knew that Johnny and Judy are dating, it would typically be sufficient for that someone to say that Judy were wearing his ring. We don't usually need to ask whether the witness had a false memory or hallucination, mistook someone else for Judy, &c. But it is important always to understand that no one just knows any complex proposition. The only things of which we have perfect knowledge are the things immediately before the mind — such as a feeling of coldness — and then we don't perfectly know their sources. Perhaps some of us are utterly reasonable in constructing models of the world to explain things such as our occasional sensations of coldness; certainly nearly all of us are so convinced of these models that we refer to a major share of their propositions as knowledge

. But none of us just knows that Johnny and Judy are dating, that it is cold outside, that his or her eyes are blue, &c. Any reasonable belief in these things is an inference ultimately resting upon primitive experience.

I don't just know how it feels to be a man. I know how it feels to be me; I have memories, which I presume to be reliable, of how it felt to be me; and part of my model of the world (constructed to explain my experience) contains adult male bodies, one of which is my body. And, to that extent, I know how it feels to be a man. When someone else tells me something at odds with my experience of being a man, I don't think Oh, maybe I'm not a man after all!

I just infer that the other person is either a man over-generalizing from his own experience or from reports, or is someone who is not a man but engaged in incompetent conjecture. I don't know how it feels to be woman. I don't even know how I would feel if I woke and found that my mind were operating in the body of a woman (which I presume would be different from how I would feel if my mind had for its whole existence operated in a female body). I simply cannot know without the experience. I could, in theory, know that I were unhappy being a man. I could, in theory, know that I wished to have a female body. But I cannot know how it feels to be a woman, and thus in no sense could I know that I somehow had a female mind in a male body. It is impossible for me to know that I am a woman. It is impossible for those who have never had a female body to know that they are girls or women. It is impossible for any of them to just know that they are girls or women. But they can certainly know their unhappiness or know their wishes. And the complement is true of those who never had the experience of being in a male body. They cannot know that they have male minds. It is impossible for those who have never had a male body to know that they are boys or men. It is impossible for any of them to just know that they are boys or men. But they can certainly know their unhappiness or know their wishes.

Hormone treatments are available to make a brain that was supposedly already female be more like an actual female brain and more as if in a female body, or a brain that was supposedly already male be more like an actual male brain and more as if in a male body. But this treatment would be actively absurd if the mind of the subject were already that of the opposite sex. I am not somehow really more a man than my levels of androgen or of testosterone or of estrogen have ever allowed me to be; likewise, I am not somehow really more a woman than my hormones have ever allowed; nor is anyone else. Those receiving such hormone treatments are not of the opposite sex; they are seeking to become more as if of the opposite sex.

If a male body could be made of a female body and vice versa, then it wouldn't matter that the female body had previously been a male body or vice versa. But present technology allows no such thing. A body that has undergone the most extensive reässignment surgery is ruined for purposes of return to its original sexual configuration. What alteration is available is primarily cosmetic, and highly destructive. Testes don't somehow become ovaries or ovaries testes; they are discarded. Breast implants may later be removed, but mammary glands become tissue to be sold or incinerated. The rest of the reproductive system is savaged.

And, if a male body could be made into a female body, or vice versa, then the change would always be something of a leap in the dark. Quite plausibly a great many people would be happy with where they landed, but others would be depressed, shocked, or horrified. With the procedures presently available — with an ultimately irreversible leap — many are indeed depressed, shocked, or horrified, without even the genuine experience of a body with a new sex. I've had at least one friend kill himself because of what he'd had done in trying to be remade into a woman. In the case of children, we are not so much considering leaping in the dark as being picked-up and thrown into the darkness. In ten, twenty, and thirty years, most of those who had been cheering the throwing will speak and write as if society were at fault in the case of those children who discovered that they'd crashed in a terrible place.

Our response to those who have come to desire interaction as if of the opposite sex should not be founded in mystical nonsense; but neither should it be characterized by condemnation or by intolerance. People should not be prohibitted from doing as they will so long as only consenting adults are involved. I think that radical treatments to change an adult's appearance to resemble that of the opposite sex are plausibly the best way for some people to alleviate very great unhappiness. I think that accommodation of such people, treating them as if they are of the opposite sex, is often quite appropriate. However, no one has a right to be treated as something that he or she is not. And, in some cases, very good reasons underlie sexual distinctions and subverting those distinctions is less humane than respecting them.

Much of the discussion of transsexualism has involved confusion — often deliberately fostered — between sex and other definitions of gender

. The use of gender

to mean sex actually dates to about the same time as it was introduced to refer to the somewhat related but distinct grammatic classification; but, for a time, use of gender

in the sexual sense fell away. It began to be repopularized for purposes of euphemism, and continues as a euphemism into the present. The grammatic sense was related to the sexual sense in that things that were male were usually named with words that had the masculine grammatic gender and things that were female were usually named with words that had the feminine grammatic gender; but many things that did not have any sex were named with words having a masculine or feminine grammatic gender even when a neuter grammatic gender was a feature of the language, and some things that had sexes were assigned names with the neuter grammatic gender. Grammatic gender was an often odd social construct.. Grammatic gender and notions of rôles appropriate to each sex each influenced the other. At some time around 1980, the idea began to catch-on of using the term gender

not in reference to sex nor in reference to grammatic gender, but to socially or personally constructed notions of those sexual rôles. The scientific and philosophic study of social or personal constructions of sexual rôles is itself very worthwhile; and the analogic appeal of extending gender

to refer to such constructions is evident. However, the pre-existing and repopularized use of gender

to refer to sex facilitated a hijacking of discourse, which confused sex with a social or personal construct of social rôle, under which hijacking it has been pretended that persons who are masculine are ipso facto male, that persons who are feminine are ipso facto female, that some males are neither male nor female, that some females are neither female nor male, and that any otherwise legitimate distinctions by sex must be replaced with distinctions by personal constructions of sexual rôle.

Of course, more than just grammatic gender or our notions of sexual rôles are here social constructs. Our language and every other language is a social construct, and the taxonomies of biology and of every other science are social constructs. More generally all taxonomies are personal or social constructs. But that does not make propositions subject to falsification by a device of recategorizing things, of exchanging labels amongst categories, or of applying new labels to categories. Rather, with a change of language a proposition is expressed differently; with a relevant change of taxonomy, a proposition involves more or fewer categories. If we adopted the convention of using Earth

to mean only the Western Hemisphere, both that and the Eastern Hemisphere would continue as they would under the old taxonomy, rather than the underlying geophysics changing. Propositions about a sex do not become false or true by the device of insisting upon a new definition of man

, of woman

, of sex

, or of gender

.

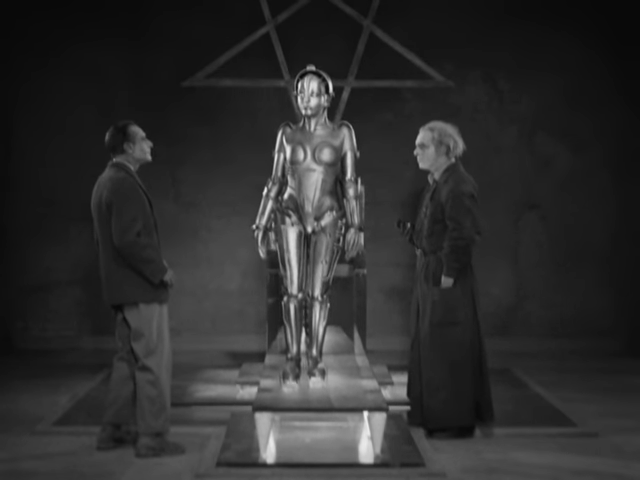

and for its depiction of a city of great skyscrapers, elevated roadways, and aircraft.

and for its depiction of a city of great skyscrapers, elevated roadways, and aircraft.  Others will remember it for what they take to be a humanistic message about the relationship between physical laborers and thought-workers being brought and kept into harmonious relations by kindness. The ideologic subtext is often unrecognized.

Others will remember it for what they take to be a humanistic message about the relationship between physical laborers and thought-workers being brought and kept into harmonious relations by kindness. The ideologic subtext is often unrecognized. At the least, this institution controls power production and water delivery. The institution seems to employ the entirety or nearly the entirety of a substantial proletariat, living and working underground.

At the least, this institution controls power production and water delivery. The institution seems to employ the entirety or nearly the entirety of a substantial proletariat, living and working underground.  The institution can act as a state in response to a violent uprising by this proletariat. Moreover, the head of the institution, Joh[ann] Frederson,

The institution can act as a state in response to a violent uprising by this proletariat. Moreover, the head of the institution, Joh[ann] Frederson,  is said to be responsible for the city more generally.

is said to be responsible for the city more generally. their living conditions impoverished. But the proletariat are lacking in intelligence and self-control. When one, Georgy 11811, is rescued by Freder (son of Johann Frederson) from labor that is overwhelming Georgy,

their living conditions impoverished. But the proletariat are lacking in intelligence and self-control. When one, Georgy 11811, is rescued by Freder (son of Johann Frederson) from labor that is overwhelming Georgy, and tasked by Freder with going to an apartment to meet with him later, Georgy instead takes money left in his care and goes to the pleasure district,

and tasked by Freder with going to an apartment to meet with him later, Georgy instead takes money left in his care and goes to the pleasure district,  even as his savior suffers in place of Georgy.

even as his savior suffers in place of Georgy.  (Freder's other disciple, drawn from the managerial class, is unfailingly faithful.) Later, with just the one exception of a foreman, each and every man and woman in the underground allow themselves to be persuaded to destroy the machinery running the city, and then thoughtlessly monkey-dance in the ruins

(Freder's other disciple, drawn from the managerial class, is unfailingly faithful.) Later, with just the one exception of a foreman, each and every man and woman in the underground allow themselves to be persuaded to destroy the machinery running the city, and then thoughtlessly monkey-dance in the ruins  even as their children face drowning when water from the reservoir comes flooding into the residential area. Plainly, one wants no dictatorship of this proletariat, nor to have them make any decisions of import.

even as their children face drowning when water from the reservoir comes flooding into the residential area. Plainly, one wants no dictatorship of this proletariat, nor to have them make any decisions of import.