The Vision of Metropolis

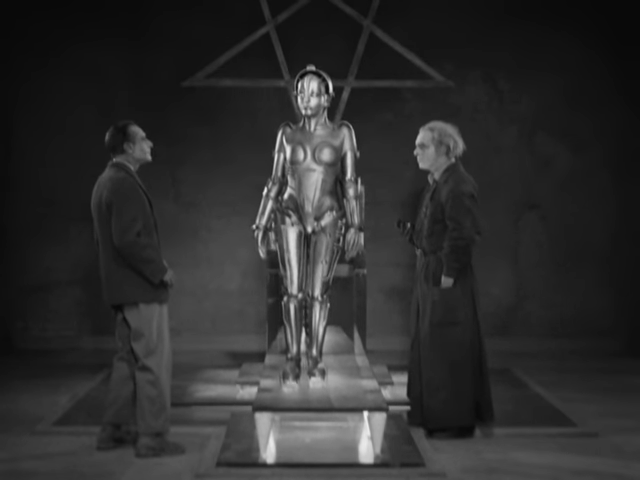

Tuesday, 10 January 2023Ninety six years ago, on 10 January 1927, the movie Metropolis premiered. Now-a-days, Metropolis is primarily remembered for its robot  and for its depiction of a city of great skyscrapers, elevated roadways, and aircraft.

and for its depiction of a city of great skyscrapers, elevated roadways, and aircraft.  Others will remember it for what they take to be a humanistic message about the relationship between physical laborers and thought-workers being brought and kept into harmonious relations by kindness. The ideologic subtext is often unrecognized.

Others will remember it for what they take to be a humanistic message about the relationship between physical laborers and thought-workers being brought and kept into harmonious relations by kindness. The ideologic subtext is often unrecognized.

Within the social order depicted in the movie, while money is a feature of the economy, that economy seems to be fundamentally technocratic. The city is under the ultimate control of a single institution, with headquarters in der neuen Turm Babel [the New Tower of Babel].  At the least, this institution controls power production and water delivery. The institution seems to employ the entirety or nearly the entirety of a substantial proletariat, living and working underground.

At the least, this institution controls power production and water delivery. The institution seems to employ the entirety or nearly the entirety of a substantial proletariat, living and working underground.  The institution can act as a state in response to a violent uprising by this proletariat. Moreover, the head of the institution, Joh[ann] Frederson,

The institution can act as a state in response to a violent uprising by this proletariat. Moreover, the head of the institution, Joh[ann] Frederson,  is said to be responsible for the city more generally.

is said to be responsible for the city more generally.

Observable, productive members of society, fall into very few classes. The narration and the female protagonist refer metaphorically to the proletariat as die Hände

[the hands

] and to a managerial class or to its leader as das Hirn

[the brain

]. Other classes are nearly irrelevant to the conception. For example, those dismissed from managerial positions are said to descend to the proletariat.

(The managerial class and proletariat are depicted as utterly male. Females employed above ground seem all to be young courtesans; females below ground are shown as living with the wage laborers, but not as employed outside the home.)

The work of the proletariat is terrible;  their living conditions impoverished. But the proletariat are lacking in intelligence and self-control. When one, Georgy 11811, is rescued by Freder (son of Johann Frederson) from labor that is overwhelming Georgy,

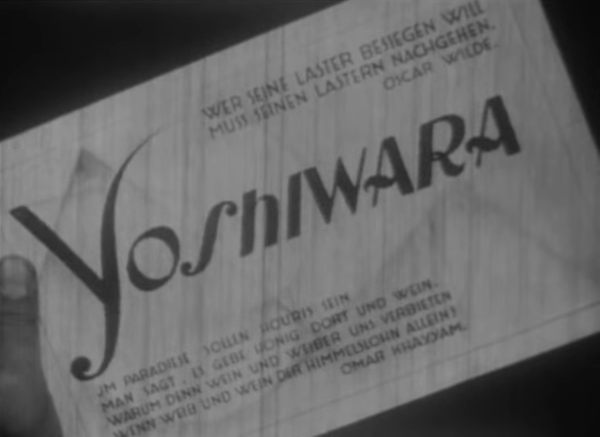

their living conditions impoverished. But the proletariat are lacking in intelligence and self-control. When one, Georgy 11811, is rescued by Freder (son of Johann Frederson) from labor that is overwhelming Georgy, and tasked by Freder with going to an apartment to meet with him later, Georgy instead takes money left in his care and goes to the pleasure district,

and tasked by Freder with going to an apartment to meet with him later, Georgy instead takes money left in his care and goes to the pleasure district,  even as his savior suffers in place of Georgy.

even as his savior suffers in place of Georgy.  (Freder's other disciple, drawn from the managerial class, is unfailingly faithful.) Later, with just the one exception of a foreman, each and every man and woman in the underground allow themselves to be persuaded to destroy the machinery running the city, and then thoughtlessly monkey-dance in the ruins

(Freder's other disciple, drawn from the managerial class, is unfailingly faithful.) Later, with just the one exception of a foreman, each and every man and woman in the underground allow themselves to be persuaded to destroy the machinery running the city, and then thoughtlessly monkey-dance in the ruins  even as their children face drowning when water from the reservoir comes flooding into the residential area. Plainly, one wants no dictatorship of this proletariat, nor to have them make any decisions of import.

even as their children face drowning when water from the reservoir comes flooding into the residential area. Plainly, one wants no dictatorship of this proletariat, nor to have them make any decisions of import.

But, using that robot, Johann Frederson deliberately had the proletariat agitated to such violence, to excuse his bringing them under more repressive control. He's not merely callous, but quite willing to do horrific things to human beings, in order to realize his vision. He only comes to recognize that he has done horrific things when he discovers that his own son may be amongst those killed.

The resolution is to be a new order in which the classes — die Hände und das Hirn — are reconciled by Freder, das Herz [the heart].

Fritz Lang, who co-scripted and directed Metropolis, was reportedly appalled to discover that the National Socialists loved the movie. Despite assurances that he would not be considered Jewish though his mother had been born a Jew, Lang fled Germany. His wife Thea von Harbou, the other scriptwriter and the author of the novelization, was not appalled, and joined the National Socialist Party after divorcing Lang.

The reason that Lang should not have been surprised is that the popular visions of fascism and of Naziism — and the vision of a better society presented by Metropolis — were of a technocratic order in which class distinctions were natural but classes were brought together in harmony. Yes, indeed, the Nation Socialists in particular wanted to wipe-out a great many people on the way to such a harmonious technocratic order, but still such an order was part of their vision.

The bottom line is not that Naziism was somehow less awful because it had the vision of Metropolis and that vision is cool. The bottom line is not that fascism is somehow cool because it has the vision of Metropolis and that vision is cool. The bottom line is that Metropolis has a fascistic vision, and so people should be goddamn'd uncomfortable if they've thought that its vision were cool. They ought to ask themselves Hey, am I, after all, a bit of a fascist?

Most people are. No one ought to be.