While the word slavery

gets used in many ways, its core meaning is that of a personal condition of being property of another person or of a group of persons

However, there are recurring attempts to redefine slavery

, insisting that a person who reaped only subsistence from his or her labor were by definition a slave. Now, this proposed definition is really orthogonal to any proper definition.

- On the one hand, a person reaps only subsistence when living with a minimal technological infrastructure in a world of markèd scarcity. Much of humankind for most of history lived with little or no production above subsistence, regardless of whether someone else were making ownership claims against them.

- In some cases, people have had lives of relative material comfort, and yet would have been tortured or killed by their masters had they sought different employment.

(Compounding the problem with the redefinition, people who are consuming commodities far in excess of their needs for survival like to redefine subsist

to include various comforts, such as electronic entertainment.)

Perhaps most of the people who abuse the world slave

in this manner do so thoughtlessly; but it ties-together with an aspect of left-wing thought to afford them a significant evasion, deceiving others and deceiving themselves. That aspect is a resistence to acknowledging a relationship between wage-rates and the amount of labor employed in an economy.

One sees this failure in present support for an increase in statutory minimum wages. What these laws really say, to put things quite simply — yet perfectly truthfully — is that if an employer or would-be employer is unwilling or unable to employ a worker at or above the statutory minimum, then the employer must fire the worker, or not hire the worker in the first place. Most advocates presume that the employer will neither fire nor refrain from hiring, as if demand for labor were perfectly inflexible.

A rather pure expression of this dissociation of wage-rates from labor employment is found in the economic model of Piero Sraffa.[1] Sraffa's work is utterly unknown to most lay-people, and unfamiliar to most economists, but to economists on the far left it is an important benchmark, exactly because it claims so much of what they want to claim. However, its persuasive success is largely a matter of subscribers failing to note or to acknowledge a great deal implicit in the model. Perhaps most remarkably, in his model, the very same amount of labor is produced and consumed with absolute disregard for the wage-rate. That is to say that workers deliver the same labor (imagined as a scalar quantity) whether they are offered literally nothing in return (not even subsistence), or all of production is given to them as wages (with the same wage-rate for each worker).

When I look at the Sraffan model, I see workers behaving as if they are slaves. When their wages provide them no more than sustenance, they are as miserable slaves; when their wages provide them less than sustenance, they are as dying slaves; when their wages provide them far more than sustenance, they are as materially comfortable slaves. What makes them seem to be slaves is that they never exercise, and thus appear not to have, any freedom of choice in where they work nor in how hard they work.

(In those states of the United States that allowed private ownership of slaves, slaves were expected to deliver some fixed quota to their owners. They were not typically offered rewards for exceeding these quotas; they were punished, sometimes horrifically, for failing to meet them. I know of no other way, in the real word, to get labor production of the sort that Sraffa describes.)

In Sraffa's model, whatever production does not go to workers, goes to the owners of the other productive resources — essentially to the capitalists.[2] If one embraces Sraffa's model or something very much like it, and if one waves-away the proper meaning of slavery

and instead uses it to mean one who is paid no more than sustenance, then it is easy to insist that, in a system that most favors a distinct class of capitalists, workers would be slaves

, whereäs alternatives decreasingly favorable to such capitalists move workers ever further away from slavery

. And if one imagines the workers getting an ever greater share exactly as production is administrated on behalf of the worker, then the movement away from slavery

is a movement towards socialism.

However, if one continues to accept a model along the lines of Sraffa, yet restores the proper meaning of slavery

, then one begins to see one why it had been doubly convenient to redefine the term. Because, in imagining a world in which workers never, one way or another, exercise freedom of choice in labor regardless of how production is distributed, the left has come perilously close to suggesting that workers, under socialism, would be slaves.

The underlying truth is that labor is one of the means of production. If an economy is fully socialized, then the potential worker must be employed however and wherever the best interests of the community as a whole are served, and his or her interests count no more in this decision than do those of anyone else.

This grim principle has repeatedly been illustrated in communities that have attempted a very high degree of socialism. Sometimes the attempt has been hijacked by leaders with less than sincere interest in communal well-being, but these leaders were able to make the populace their slaves because socialism required slavery of the populace. Trotsky's observation that

The old principle: who does not work shall not eat, has been replaced with a new one: who does not obey shall not eat.[3]

was true under Stalin because it or something like it would, as a practical matter, have been true under any fully realized socialism.

Meanwhile, as much as many people living in more market-oriented economies like to imagine themselves as slaves to their employers, they're fully aware that these employers cannot send agents to recapture them should they quit their jobs. To the extent that any group of persons other than ourselves exercises such ownership over us, that group is the state — the very institution usually entrusted to effect socialistic measures.

A movement towards socialism is a movement towards slavery, rather than away from it, and if one is going to bring the subject of slavery into an honest defense of socialism against all alternatives, then it is necessary somehow to make a case for slavery.

[1] The Production of Commodities by Commodities; Prelude to a Critique of Economic Theory (1960).

[2] Note how advocates of higher statutory minimum wages point with outrage at those who amass great wealth while paying workers less that some proposed statutory minimum wage, as if there were a zero-sum game being played between employer and employee.

[3] The Revolution Betrayed, ch 11 Whither the Soviet Union?

§ 2 The Struggle of the Bureaucracy with the Class Enemy

.

![[formal logical expression]](wp-content/uploads/2015/09/not_not_know_why_like_hitler.png) So,

So,

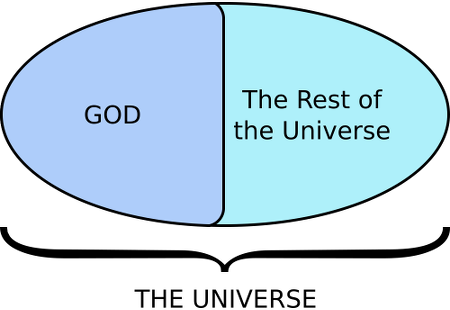

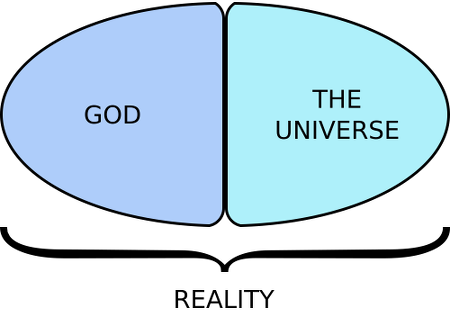

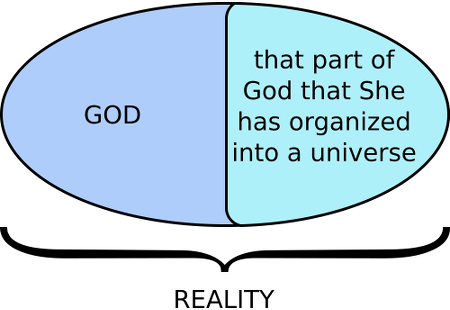

However, a lot of theïsts want to assert that G_d is outside of what they call

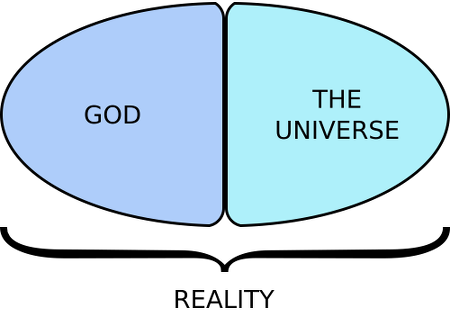

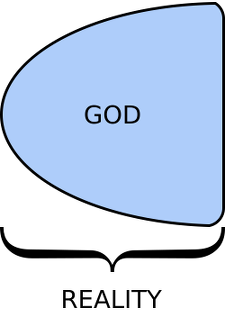

However, a lot of theïsts want to assert that G_d is outside of what they call  Likewise, for those who more generally claim that G_d not is not entirely contained by what they call

Likewise, for those who more generally claim that G_d not is not entirely contained by what they call

or perhaps within Her (in which case we might speak and write of two parts, one of them being the universe, and the other being the rest of G_d)

or perhaps within Her (in which case we might speak and write of two parts, one of them being the universe, and the other being the rest of G_d)  or perhaps partially internal to Her and partially external.

or perhaps partially internal to Her and partially external.