Ill-Remembered History

1 June 2009Recently, I began watching The Stranger (1946) for the first time in many years.

There are many things that one might say about this film, and in particular about the sociological aspects of this film. Here, I want to draw attention to one in particular.

Here's a clip:

On another page, I provide a fairly full transcription of the dialogue for the whole clip. Here, let me focus on a shorter excerpt from within this clip.

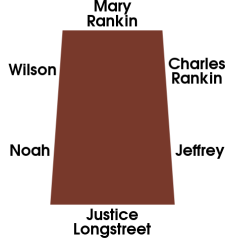

| Mr Wilson | (Edward G. Robinson) | … | undercover agent of the Allied War Crimes Commission |

| Franz Kindler aka Charles Rankin | (Orson Welles) | … | fugitive Nazi official, living under an assumed identity |

| Adam Longstreet | (Philip Merivale) | … | Justice of the SCotUS |

| Mary Rankin née Longstreet | (Loretta Young) | … | daughter of Judge Longstreet, newlywed bride of Charles Rankin |

| Noah Longstreet | (Richard Long) | … | son of Justice Longstreet |

| Jeffrey Lawrence | (Byron Keith) | … | town doctor |

| Red | (unknown) | … | Mary's dog |

Wilson: Do you know Germany, Mr. Rankin?

Charles: I'm sorry, I— I have a way of making enemies when I'm on that subject. I get pretty unpopular.

Wilson: Well, we shall consider it the objective opinion of an objective historian.

Charles: Historian? A psychiatrist could explain it better. The German sees himself as the innocent victim of world envy and hatred — conspired against, set upon by inferior peoples, inferior nations. He cannot admit to error, much less to wrongdoing, not the German. We chose to ignore Ethiopia and Spain, but we learned, from our casualty list, the price of looking the other way. Men of truth everywhere have come to know … for whom the bell tolled. But not the German. No, he still follows his warrior gods, marching to Wagnerian strains, his eyes still fixed upon the fiery sword of Siegfried. And [glances at Jeffrey] in those subterranean meeting places that you don't believe in, the German's dreamworld comes alive and he takes his place in shining armor, beneath the banners of the Teutonic Knights. Mankind is waiting for the Messiah; but, for the German, the Messiah is not the Prince of Peace. No, he's… 'sanother Barbarossa, another Hitler.

Wilson: Well, then, you, uh, you have no faith in the reforms that are being effected in Germany.

Charles: I don't know, Mr. Wilson. I can't believe that people can be reformed except from within. The basic principles of equality and freedom never have, never will take root in Germany. The will to freedom has been voiced in every other tongue [Wilson nods.] —All men are created equal,liberté, égalité, fraternité— but in German—

Noah: There's Marx:Proletarians, unite. You have nothing to lose but your chains.

Charles: But Marx wasn't a German; Marx was a Jew.

Justice Longstreet: But, my dear Charles, if we concede your argument, there is no solution.

Charles: Well, sir, once again, I differ.

Wilson: Well, what is it, then?Charles: Annihilation. Down to the last babe in arms.

Mary: Oh, Charles, I can't imagine you're advocating a … Carthaginian peace.

Charles: Well, as an historian, I must remind you that the world hasn't had much trouble From Carthage in the past … 2,OOO years.Justice Longstreet (chuckling): Well, there speaks our pedagogue.

Mary: Well, uh, speaking of teachers, Mr. Wilson, …

Wilson: Yes, huh?

Mary: The faculty is coming for tea next Tuesday. If you have nothing better to do, would you like to join us?

Wilson: Uh, I'd like to, but my work here is finished. [Charles smiles faintly.] I'm leaving Harper tomorrow.

(Later, Charles and Mary Rankin enter their home.)

Mary: Extraordinary, isn't it, clocks being Mr. Wilson's hobby, too?

Charles: Yes, isn't it?

Mary: Well, Red, how do ya like your new house?

Charles: He loves it. Come here, Red; I think I'll take you for a walk. Come here, boy.

Mary: Oh, darling, you don't have to take him out. Just let him out. He won't run off.

Charles: I need the walk; I'm restless. Come on, boy.

(At Wilson's room.)

Male voice from phone: That's good. How are you coming along?

Wilson: I'll be in Washington tomorrow afternoon. You were right about Rankin. He's above suspicion.

Notice that Professor Rankin has advocated genocide — wiping-out the Germans Down to the last babe in arms.

The only person at the table who raises the slightest objection is Mary, and even her response is mild. Wilson, the principal hero of the story, concludes from this advocacy that Professor Rankin is above suspicion

— the emphasis on above

is Wilson's — rather than, say, a pathological Germanophobe.

When Americans remember the war and its aftermath, we tend to forget that there was a time when preaching genocide, while a minority position, was socially acceptable. In fact, such sentiment reached up to the highest levels of government. Here are a couple of excerpts from The New Dealers' War by Thomas Fleming (which excerpts may be familiar to those who followed my LJ):

New Dealers and others around the president made no attempt to alter this dehumanizing war against the Japanese. In September 1942, Admiral William Leahy, Roosevelt's White House chief of staff, told Vice President Henry Wallace that Japan was

[…]our Carthageandwe should go ahead and destroy her utterly. Wallace noted this sentiment without objection in his diary. Elliot Roosevelt, the president's son, told Wallace some months later that he thought Americans should killabout half the Japanese civilian population. New Dealer Paul McNutt, chairman of the War Manpower Commission, went him one better, recommendingthe extermination of the Japanese in toto.At the White House on August 19, 1944, [Secretary of the Treasury] Henry Morgenthau told Roosevelt the British were much too benevolent in their postwar plans for Germany and so were the State Department and the European Advisory Commission. The Secretary was, incidentally,

shockedby FDR's appearance.He is a very sick man and seems to have wasted away,he told his diary. But that observation did not deter him from urging the president to stop this soft approach to Germany.Roosevelt's animus against the Germans erupted into fury.

Give me thirty minutes with Churchill and I can correct this,he told Morgenthau.We have got to be tough with Germany and I mean the German people, not just the Nazis. You either have to castrate [them] or you have got to treat them … so they can't just go on reproducing people who want to continue the way they have in the past.Morgenthau left the White House convinced that he had a mandate to create a better plan to deal with postwar Germany. He put Harry Dexter White in charge of a special committee

to draft the Treasury's analysis of the German problem. The result was the Morgenthau Report. It proposed to divide Germany into four parts. It also recommended destroying all the industry in the Ruhr and Saar basins and turning Central Europe and the German people into agriculturists. At one point Communist agent White, who was described by his Soviet handler asa very nervous cowardly person, feared they were going to extremes. He warned Morgenthau this ideal was politically risky; it would reduce perhaps 20 million people to starvation.I don't care what happens to the population,Morgenthau said.

Tags: cinema, Edward G. Robinson, FDR, film, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, genocide, Germany, Harry Dexter White, Henry Morgenthau, Henry Wallace, Morgenthau Report, movies, Orson Welles, William Leahy, World War II

Interesting piece. I replied to your comment on my site, but it bears repeating that I think Welles deliberately had a Nazi, Kindler, expouse those ideas in order to shine a critical light on them (however fleeting).

All that said, I think given the bloody, life and death struggle the U.S. had just come out of, that sort of post-WW2 reactiontion was understandable. That we instead chose other paths (Marshall Plan, Truman Doctrine) is only to our credit.

You're basically interpretting Welles as presupposing that the audience would watch the film with the eyes and ears of intelligent, critical thinkers. This would be an unnatural reading in any case; and, after his experience about eight years earlier with The War of the Worlds, especially implausible for Welles.

Genocide was being advocated from very early in the war. The advocates were always a minority, but some of them were quite prominent, and some were well positioned to know that the Roosevelt had manœuvred the United States into the war, and turned the war into a struggle by such things as insisting on unconditional surrender (an insistence that was not only counter-productive, but in fact ultimately waived by Truman in the case of Japan).

You're basically interpretting Welles as presupposing that the audience would watch the film with the eyes and ears of intelligent, critical thinkers.

Not at all. First of all, not that it really matters, but there's a school of thought (fueled by Welles himself in an interview late in life) that rather than being surprised by public reaction, the WOTW broadcast was a dilberate effort on Welles and the Mercury Theater's part to show how effective mass media could be.

In any event, I'd still argue that Welles made films for himself not his audience. For his first film, he could have easily made a commercially viable version of WOTW and instead choose to do the much more ambitious (and risky) Citizen Kane.

The Stranger wasn't meant to be a great work as much as proof that he could churn out a film on time and within budget after the Ambersons fiasco. That said, Welles brand of social commentary was usually even handed and often ahead of the curve. For instance, he dealt with illegal search and seizure and questionable police interrogations years before the Miranda decision in Touch of Evil.

To the extent that Welles were making any film for himself and not for the rest of the audience, he simply wouldn't be motivated to , as he would already be aware of the point. Further, there would be quite the contradiction in Welles both seeking to comment — if only to himself — that this opinion were evil, but to present the commentary in a form such that, not only would it be missed by the audience, but the opinion would would actually be promoted.

As to the purpose of The War of the Worlds, in an appearance on Nightline Welles claimed that his intent had been to undermine the credibility of Father Coughlin, by proving that what was said on the radio needn't be true. For various reasons, I view that claim (about intent) with skepticism.

To the extent that Welles were making any film for himself and not for the rest of the audience, he simply wouldn't be motivated to shine a light, as he would already be aware of the point.

Why not?

While I don't see The Stranger as anything more than a B or B+ movie, I still think it's telling that Welles having a NAZI champion the genocide solution. Res ipsa loquitur.

Motivation is something positive, rather than an absence of a counter-argument.

Indeed it's telling, but the viewer of to-day will typically misunderstood what it says.

Motivation is something positive, rather than an absence of a counter-argument.

Then I'll be more specific. You've created an interesting logical box out of my previous comments. But one that ultimately doesn't hold water. You provide NO basis on which to argue the position that because Welles was already aware of a particular idea, he'd have no reason to explore that on film.

Now you're waling on a straw-man. I haven't claimed that because Welles was already aware of an idea he had no reason to explore it on film; rather, I've argued that if he had sought to explore it on film then he would not had explored it by producing the sort of scenes that these are, and the sort of film that The Stranger is.

One on something to change perceptions. Welles wouldn't have been plausibly trying to change his own perceptions. He would have understood how the film would look and sound before he shot it, and there isn't much room for a change of perceptions if one has already grasped the idea that you read into this film.

If Welles were going to , it would be to change the perceptions of some share of the rest of the audience. But, as I've noted, at the time that this film was produced and released, its effect would have been to promote the idea that those who advocated genocide were merely over-zealous, and as Nazi-types — unless, apparently, they slipped on something such as a question of Jewish nationality.

The of this film is in that , which would be a different conjunction if a light had been shown on the point that advocating the annihilation of the German people was much like what had been taken as unacceptable in Naziism.

Now you're waling on a straw-man. I haven't claimed that because Welles was already aware of an idea he had no reason to explore it on film;

In all honesty, the way I read your comments, you did.

I said: In any event, I'd still argue that Welles made films for himself not his audience.

To which you replied (echoing my words): To the extent that Welles were making any film for himself and not for the rest of the audience, he simply wouldn't be motivated to shine a light, as he would already be aware of the point.

I'm not sure how else to interpret that response other than indicating that because Welles already held a certain position, he'd have no reason to explore it on film.

However, I'll put that aside and take up what you clarify as your true argument:

rather, I've argued that if he had sought to explore it on film then he would not had explored it by producing the sort of scenes that these are, and the sort of film that The Stranger is.

Again, I've maintained from the start that The Stranger is more potboiler than great art. So, in many ways we're probably giving it more thought than Welles did.

I don't think it can really be proven one way or another HOW Welles would explore an idea on film. He injected pathos and sympathy into two of his best known villians: Harry Lime and Hank Quinlan - both characters who Welles described as evil.

You make much out of Wilson's inability to see through Kindler's disguise even after his proposed "final solution" for Germany as proof that such a position advocating genocide wouldn't seem out of place. Fair enough. However, I still see it as a small moment of deliberate irony injected by Welles (which is totally consistent with his style as demonstrated in other works). Also, the context in which I interpret the dinner exchange is much differently than you.

We may disagree, but for me the entire scene comes off as more of an academic exchange between Rankin and the others where he himself acknowledging that no one is seriously going to consider his point of view. I also don't agree that Mary's reaction was "mild." Justice Longstreet (an actual government official) wryly dismisses Rankin as a "pedagogue" whose ideas were merely the theorical musings of a cloustered professor rather than a serious policy maker.

Part of Wilson's initial feelings about Rankin may have been BECAUSE he couldn't believe that a true war criminal such as Kindler would be able to so successfully immerse himself in such respected company. Sure, Rankin may be a bit "out there," but it's not enough to hang him. While he said on the phone that Rankin was "above suspicion," Wilson certainly had subconscious doubts about Rankin which bubbled to the surface as he slept.

That German genocide was seriously considered position at the time is a very interesting point and certainly can be said to have played into Wilson's evaluation. However, I don't agree that The Stranger in any way validates that idea.

When I wrote (as you quote)

the crucial difference is explicit. Welles could have a reason if he had an audience other than just himself.

Quite probably. I certainly don't believe that Welles was thinking of this scene as one that would treat the advocacy of genocide as it does.

That depends upon the standard of proof appropriate ot the discussion. I don't think that, say, the standards of deductive logic or of criminal justice are approrpiate.

And I think that he does a respectable job of making Kindler seem human.

And I would agree that far.

I've no doubt of that.

And I would also agree that far. But such an academic discourse will fit in some sorts of wider contexts, but not in others.

Part may have been, but the dinner scene gives Wilson's reäctions, expressed as nods and other body language, to the speech. Wilson is plainly sympathetic to it some of its nonsense. And he is depicted as having concluded that Rankin is not Kindler at the close of Rankin's argument for genocide. The dinner scene is only continued long enough to show that Wilson has reached this conclusion. (We don't, for example, get to hear Rankin tell a touching story over dessert.)

The movie associates these exactly and only with the issue of denying that a Jew could be a German. It certainly had opportunity for Wilson to indicate that, upon further consideration, the advocacy of genocide was worrisome, but it never took hold of that.

It doesn't agree with the advocacy of genocide; but it treats it like being a bit more royalist than the king.