Ungodly Answers

Wednesday, 26 August 2015I've recently posted a couple of entries that bear upon belief in G_d. In one, I noted how it is that we may have a legitimate sense that some events are guided by a purpose, which purpose is not that of any human being, yet is after all also not that of gods either. More recently, I challenged the notion that morality must or even can originate in commandments of G_d.

It isn't my intention to produce a parade of entries about G_d, nor to deal with the subject comprehensively in this 'blog. But the theme of G_d has been on my mind enough to provoke this one further entry. Like the previous two entries, this one will critique an argument for the existence of G_d, but will not attempt a disproof of that existence. I would be surprised if any of the reasoning that I provide in this entry were novel, but I hope that my exposition will be helpful.

One of the reasons that people believe in G_d is that they believe that She provides an explanation for the existence of the universe.

Part of the problem here is in being a bit careless about to what one refers with the word universe

; that word has multiple meanings.[1] It would be abusive to presume that a theïst were using one of the narrower meanings — a currently closed set of interacting energy and matter — and show how that which we inhabit could have been creäted by previous mindless processes within some larger cosmological system. The theïst would naturally and rightly insist that by universe

he meant that larger system.

For purposes of this sort of discussion, I think that, by universe

, we really ought to mean reälity.  However, a lot of theïsts want to assert that G_d is outside of what they call

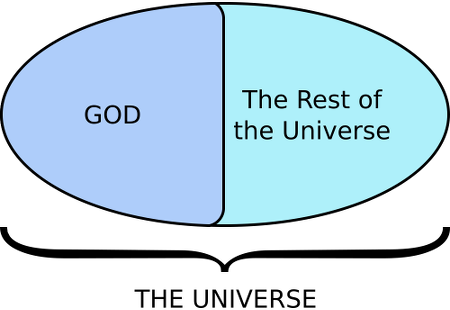

However, a lot of theïsts want to assert that G_d is outside of what they call the universe

. Now, saying X is outside of reälity

is really saying that there is no X, that there's no more than an idea which is not instantiated. Plainly, when theïsts say that G_d is outside of what they call the universe

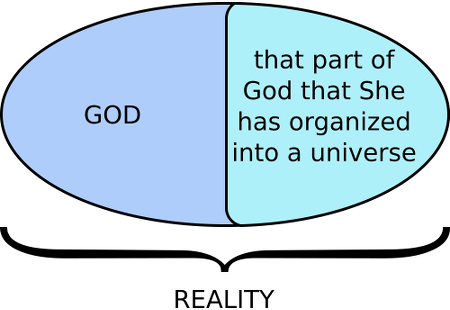

, they don't mean that She is unreal; they must mean to divide reälity into at least two parts, one of which is G_d, and the other of which is something that they call the universe

.  Likewise, for those who more generally claim that G_d not is not entirely contained by what they call

Likewise, for those who more generally claim that G_d not is not entirely contained by what they call the universe

, though all or part of it might be within Her; they do not mean that the remainder of G_d is unreal!

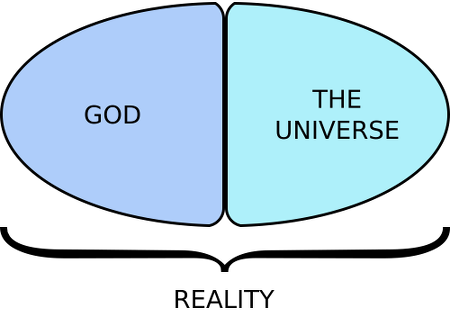

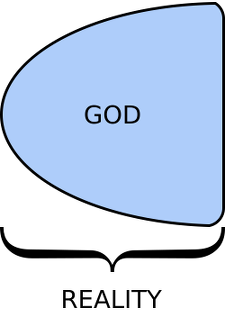

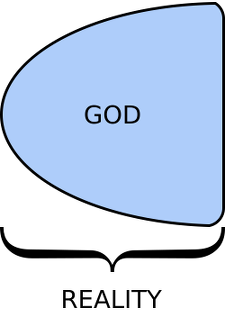

What they're claiming is that, at one time, reälity was just G_d,  and then She brought that which they call

and then She brought that which they call the universe

into existence, perhaps external to Herself  or perhaps within Her (in which case we might speak and write of two parts, one of them being the universe, and the other being the rest of G_d)

or perhaps within Her (in which case we might speak and write of two parts, one of them being the universe, and the other being the rest of G_d)  or perhaps partially internal to Her and partially external.

or perhaps partially internal to Her and partially external.

But if, instead of asking what brought the universe

into existence, we ask what brought reälity into existence, then we've not yet got an answer. We have G_d, sitting there,  unexplained.

unexplained.

Now, most theïsts are of the view that there was no time when G_d did not exist. Perhaps they imagine that an eternity has already passed; perhaps they imagine that time had a beginning, and G_d were there. Either way, if that is an acceptable claim about G_d, then it is not clear why it would not be an acceptable claim for an impersonal cosmological system. Likewise for just winking into existence ex nihilo after the passage of some time, if such a proposition (entailing the passage of time with nothing to change!) were coherent.

And a claim that G_d is the Great Mystery (accompanied perhaps by a beatific smile) is no explanation at all.

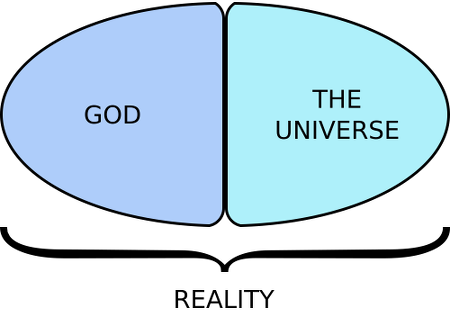

The introduction of the idea of G_d simply begged the question of whence it all came. The begging of the question is compounded if reälity is imagined as in two parts, one of which is G_d and the other is taken to be defined as creäted. Separating reälity into two parts, one G_d and the other called the universe

allowed this group of theïsts to confuse and to be confused.

The question of why the universe should be lawful — why there's logic and math and why various things have physical properties and so forth — is often mistaken for a question distinct from that of whence came reälity. But any thing exists exactly to the extent that it has properties; in a sense, a thing is what it does. When we describe what a thing does, we give its properties; this is no more or less than describing its laws; the most general laws describe the widest collections of things. (A friend once objected that logic did not seem to be a property of any thing; I told him that logic corresponds to properties of everything.) While it would seem that the universe might in many cases have very different laws, the idea of a law-less universe is incoherent.

[1] Some or all of these meanings have been noted by cosmologist John D. Barrow in The Book of Universes. Unfortunately, in other discussion, Barrow himself is sometimes unclear as to which definition he is employing.